Understanding Food Noise & The Mental Chatter Fueling Binge Eating Disorder

As a psychotherapist with expertise in binge eating disorder (BED), over the years clients have consistently described the experience of an intrusive and relentless mental chatter about food and eating that dominates their thoughts and depletes their energy, often resulting in a binge followed by feelings of failure and shame. More recently, clinical and medical communities have coined the phrase food noise to describe this experience. While it has always been a central feature of binge eating disorder, understanding food noise and its relationship to BED has become crucial for both those who experience it and the therapists who support them.

What Is Food Noise?

Food noise refers to the persistent, intrusive thoughts about food that occupy mental space throughout the day. These aren't casual musings about what to have for dinner or pleasant anticipation of a favorite meal. This monster is far more pervasive and operates in the shadows, fueling feelings of inadequacy and shame. For many, these thoughts are experienced as intrusive, all-consuming, and can feel very isolating. Historically, binge eating has been attributed to impulsively and occurring without forethought, planning, or consideration of things like calories consumed.

The widespread use of GLP-1 receptor agonists has changed this landscape in an unexpected way. As patients began reporting that these medications quieted the relentless mental chatter about food, the term "food noise" emerged and has rapidly gained popularity as people experienced, many for the first time, language that captured an experience that previously thought they alone experienced. Food noise can manifest in planning when, what, and how to access food without detection, worrying about what has already been eaten, and calculating calories. Those with binge eating disorder may have rigid (and often arbitrary) rules regarding food consumption. This then forces them to negotiate the cognitive dissonance that follows when they violate one of their one rules. For example, someone struggling with binge eating may put in place a boundary separating good food days from bad food days, using midnight as a new day, wiping the slate clean, and affording them another opportunity to prove to themselves they can exercise control.

For some people, food noise is a low hum in the background of daily life. For others, particularly those with binge eating disorder, it becomes a deafening roar that makes it nearly impossible to focus on work, relationships, or anything beyond the next opportunity to engage with food. The intrusive quality of these thoughts can feel distressing, overwhelming, and foster a feeling of being out of control—as if a prisoner of your own mind.

Normal Hunger vs. Food Noise

It's important to distinguish between the organic hunger cues that everyone experiences and the more intrusive experience of food noise. From a biological perspective, we are hard wired to experience normal hunger cues as this is essential to our drive to survive. Food noise, however, is compulsive and deeply rooted in anxiety. These persistent thoughts don't feel like neutral information or pleasant anticipation; they feel demanding, shameful, and difficult to redirect. The cognitive energy of the mental gymnastics required to manage food noise can be exhausting, leaving people feeling mentally depleted even when they have not engaged in strenuous physical activity. For individuals with binge eating disorder, food noise isn't just an occasional annoyance—it's often a defining experience that persists throughout each day.

The Intersection of Food Noise and Binge Eating Disorder

Binge Eating Disorder is defined by recurring episodes during which an individual consumes a large amount of food in a relatively short time, coupled with the feeling of being unable to stop or interrupt the binge. Following a binge, the individual experiences considerable emotional distress, which often includes deeply rooted shame (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). While this clinical definition is helpful for clinicians, it’s important to note that the clinical criteria completely fail to capture what many people with BED grapple with each day: the relentless mental preoccupation with food that fills the space between binge episodes fueling the cycle between episodes. Additionally, the criteria doesn’t account for the ways in which binge eating profiles vary significantly across clients.

The Binge Cycle

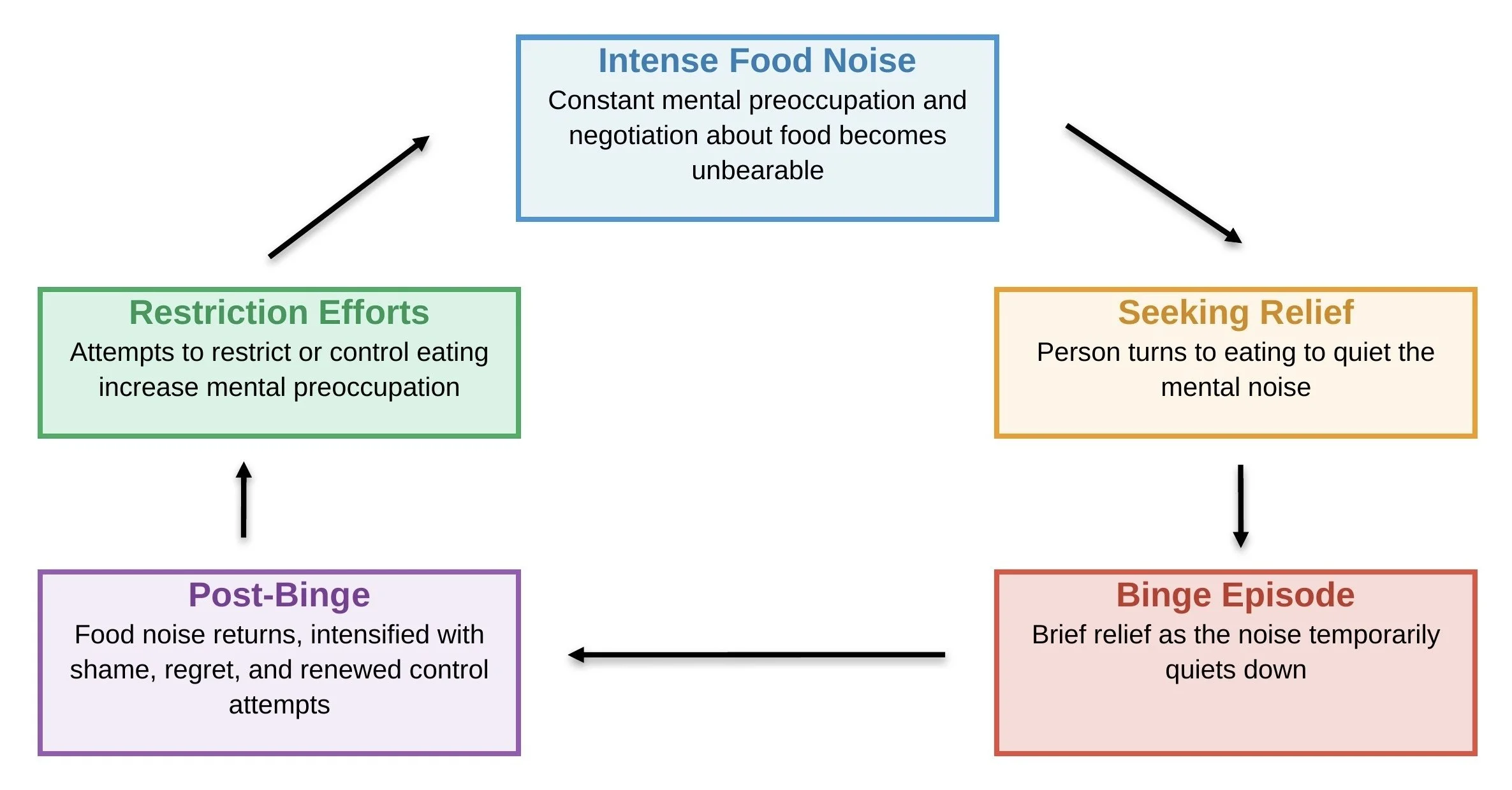

To understand the relationship between food noise and binge eating, we first need to understand how the binge cycle functions and the way in which this pattern is reinforced over time. Food noise can trigger binge episodes by creating such intense mental preoccupation that the person eventually seeks relief through eating. The constant mental negotiation about food becomes unbearable, and a binge episode offers brief relief as the noise quiets down. Unfortunately, this relief is short-lived. After a binge, food noise typically intensifies again, now layered with shame, regret, and renewed determination to restrict or control eating. This sets up a cycle where food noise leads to binging, which leads to more food noise, which leads to more binging.

Research has shown that this cognitive preoccupation with food is a significant maintaining factor in BED. Studies examining these cognitive processes have found that individuals with BED demonstrate heightened attentional bias toward food cues and increased difficulty disengaging from food-related thoughts (Svaldi et al., 2010). It’s important to understand that this is not a simple matter of willpower; it reflects genuine neurobiological differences in how the brain processes reward, impulse control, and emotional regulation.

Food noise, and even binging behavior, are symptomatic of a broader struggle that has little to do with food itself. The complex underbelly of BED includes thoughts and feelings that reflect the experience that stems from chronic attempts to control one’s relationship with food, moral judgments about "good" and "bad" foods, anxiety about body size or weight (often beginning in early childhood), and deep feelings of inadequacy and shame. For many, efforts to exert control through food management can be an attempt to experience a sense of control in one area, when other areas of one’s life may feel unpredictable, uncontrollable, and unbearable.

Living a Double Life

Many of my clients with BED describe feeling like they're living a double life. Outwardly, they may appear highly functional, managing careers, families, and responsibilities with apparent ease. Internally, however, they're engaged in a constant and exhausting battle with the internal chatter that simply won't loosen its grip. For example, someone may smile and nod during a conversation while simultaneously calculating how many hours until they can get home to eat, how they will access the food, and how they can engage in a binge without detection.

This cognitive burden is an isolating experience and is invisible to others, but it profoundly impacts an individual's quality of life, sense of self, and mental health. The mental and emotional energy required to maintain this facade—appearing "normal" around food while internally struggling—leaves people depleted and disconnected from authentic engagement with their lives. Many describe feeling like an imposter or a fraud, as though their competent exterior is concealing something within them that is fundamentally broken. This disconnect extends to relationships, where the inability to share what's really happening internally impairs the ability to experience real connection

Ironically, feelings of isolation and invisibility often occur simultaneously with an intense fear that the secret one holds can be discovered by others at any time. Clients describe hypervigilance around eating in front of others, anxiety about evidence of binge episodes being found, and elaborate measures to hide food purchases or consumption. This paradox—desperately wanting to be seen and understood while simultaneously terrified of exposure—creates additional psychological distress and reinforces the shame that contributes to keeping the cycle of BED active. The fear of judgment, rejection, or being perceived as lacking self-control keeps many people suffering in silence for years before seeking help.

A Path Forward

Therapy offers a vital lifeline for clients suffering with the dual burden of binge eating disorder and unrelenting food noise. Perhaps the most fundamental gift of the therapeutic relationship is the opportunity to finally be truly seen by another without judgement or shame. For many clients, therapy represents the first time they've spoken openly about their struggles with food, ending years of silence and hiding. In this safe, confidential space, we will safely explore the feelings of shame that have kept you isolated. When we begin to tell our truth in spaces that feel safe, feelings of shame begin to lose their power. Our work together is designed to allow you to experience yourself in a dynamic way that reframes your relationship with food, with your body, and with yourself.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Svaldi, J., Tuschen-Caffier, B., Peyk, P., & Blechert, J. (2010). Information processing of food pictures in binge eating disorder. Appetite, 55(3), 685-694.