The Stigma of GLP-1 Medication for Weight Loss

In recent years, the popularity of GLP-1 medications, such as Wegovy, Ozempic, or Zepbound, has gained popularity as medication to treat some of the most challenging behavioral symptoms of Binge Eating Disorder (BED). While GLP-1 medications have shown remarkable promise, clients considering such medications often experience significant feelings of shame, judgement, and the fear of being perceived by others as lazy, undisciplined, or “taking the easy way out.”

The conversation surrounding GLP-1 medications and BED inevitably intersects with cultural attitudes about weight, body size, and health. While the decision to take any medication is a very personal decision, and one that should only occur with physician oversight, clients often fear that if they disclose their choice to healthcare professionals, family, close friends, or even therapists, they will receive an unfavorable or unsupportive response.

The feelings of fear and shame around taking GLP-1 medications do not emerge in a vacuum—they reflect deeply ingrained cultural narratives about weight, willpower, moral character, and worthiness that have been woven into clients’ beliefs about eating, body size, and health for generations. Messages from the media further contribute to the mixed messages we receive about our bodies as the media oscillate between celebrating these medications as “revolutionary” and a weight loss “solution,” and condemning them as a dangerous shortcut that enables people to avoid doing the “hard work” of sustainable behavioral change.

As GLP-1 medications have gained popularity within celebrity circles, the media discourse has become one of a value-based framework—clients are either empowered, or the medication use reflects a shameful surrender to vanity and laziness. For individuals struggling with binge eating disorder, this polarized conversation creates an additional psychological burden at a time when they already feel particularly vulnerable.

Social media serves as a unique platform where the users themselves contribute to providing constant background noise that normalizes shame and pathologizes normal eating. While some social media content can communicate messages of support, it can be a double-edged sword because clients with BED often present as hypersensitive to feelings of shame. For the person surrounded by before-and-after photos and "what I eat in a day" content by families, friends, and influencers can ignite feelings of shame and anxiety, while reinforcing the dangerous message about the superiority of thinness.

The Burden of Shame

Individuals who struggle with food, their weight, and their relationship with their body often carry years, if not decades, of internalized narratives attributing their eating patterns to personal failure, a lack of discipline, or moral weakness. Over time, many of those messages are internalized resulting in intense self-criticism—all predicated on the assumption that if they simply tried harder or had greater resolve, success would follow. When these approaches fall devastatingly short, the feelings of personal inadequacy are reinforced. Against this backdrop, considering medication can feel like a final admission of defeat rather than a legitimate treatment decision.

Shame around food and body size doesn't originate in a vacuum—the messages are carefully constructed through layered external messages that often begin remarkably early. Even in my own practice, children as young as three years old have demonstrated internalized messages about food, evidenced in language about “good foods” versus “bad foods,” as well as value-based statements about body size. It’s important to consider that the majority of parents have unconsciously communicated these messages in ways they aren’t even aware of. Well-meaning parents may police portions, comment on weight gain that is often associated with normal development, or praise weight loss. Parents may restrict certain foods or inadvertently model their own dysfunctional relationship with food and their body by making self-deprecating remarks about their own body and modeling restrictive behavior around foods they perceive to be a trigger to binging.

When Practice and Reality Collide

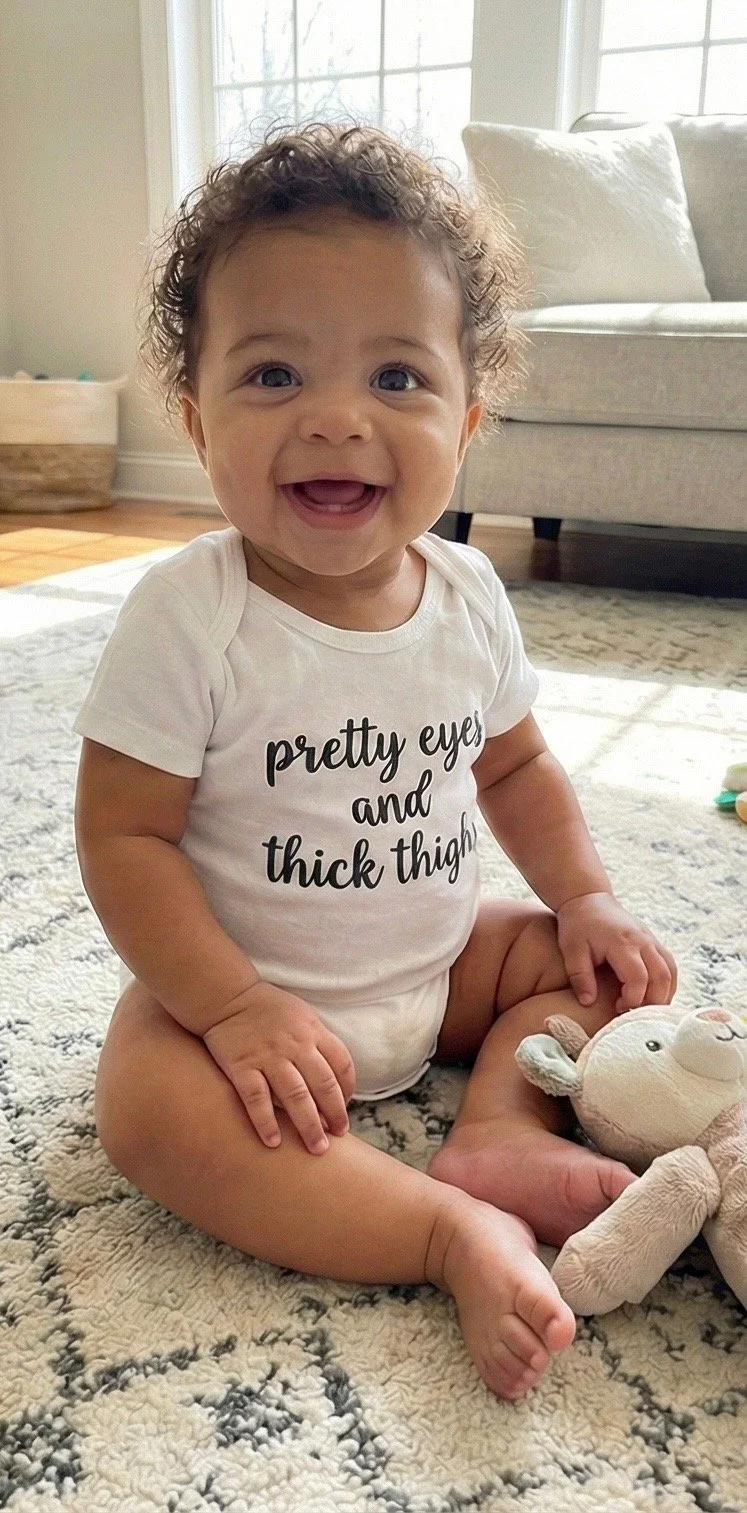

Nearly eight years ago, I stepped into the most important and fulfilling roles I have experienced when I became the aunt to beautiful (identical) twin girls. In spite of my clinical experience and expertise, I admit I was taken aback when a mutual friend one day stopped by with matching onesies that read, “beautiful eyes thick thighs.” The intention of the gift was unquestionably offered with the best of intentions, and yet I couldn’t help but also recognize and appreciate that although my nieces were only a few weeks old, society had already identified its next target. While this could easily be dismissed as an isolated incident, far too many clients have shared childhood memories with startling clarity: a grandmother pinching their stomach and saying "we need to watch this," a birthday gift of “Fen-Phen,” a parent putting them on a diet while their siblings ate freely, being praised for eating less or losing weight, or watching their mom step on the scale daily and then declare whether she, herself, is "good" or "bad" based on the number. Certainly, adults who grew up and never developed Binge Eating Disorder have shared similar experiences. At the same time, these early experiences are powerful and often occur at a developmentally critical time when children are looking to their parents to reflect back to them their self-worth is conditional on their body size.

An Individually Tailored Approach

The stigma of taking GLP-1 medications exposes a pervasive underbelly that feeds on the vulnerability of an already marginalized group. As a psychotherapist specializing in BED, I've spent hundreds of hours sitting with clients helping them untangle the intricate web of internalized shame over food and their bodies, which is often intensified as they evaluate whether or not to utilize GLP-1 medication to support their individual goals. What becomes clear, session after session, is that BED is rarely just about food. Binge eating is merely a symptom of the crushing weight of shame that so many carry through the world—and yet, your body is not a problem to be solved. The decision to utilize medication to support your personal health goals does not reflect personal weakness, moral failing, or insufficient effort.

If you are looking for a safe space to begin to explore your relationship with food, contact Bren for consultation. You deserve comprehensive care that alights with your personal values, goals, and circumstances without judgment.

*Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment recommendations. This article does not replace consultation with a qualified healthcare professional.